In most African countries, there continues to be a disconnect, even gulf at times, between what is on the law books on the one hand, and meaningful enforcement thereof on the other. This is of course not unique to Africa, but remains nevertheless prevalent on the continent. That disconnect is not unique to anti-corruption legislation, however; the same is true of many other branches of complex or ‘contentious’ law throughout Africa, including taxation law, environmental law and labour law. This factor is crucial to anti-corruption endeavours in Africa. This article will analyse how such a disconnect pans out in three case studies: Madagascar, South Africa and Kenya.

Madagascar: An institutional anomaly

Madagascar offers an example of this disconnect between anti-corruption legal initiatives and enforcement hindrances. In the case of Madagascar, it is an institutional anomaly that is a leading concern. The country has a court that was specifically set up for corruption cases, the Pôle Anti-Corruption (PAC), which works somewhat in tandem with the country’s investigative body, the Bureau Indépendant Anti-Corruption, or BIANCO. However, in 2018 the government established the Haute Cour de Justice (High Court of Justice), or HCJ. Only the HCJ can hear any cases brought against the country’s president, members of government, leaders of parliament and members of the Constitutional Court in relation to their duties. Critics have argued that this seriously undermines the effectiveness and even mandate of the PAC.

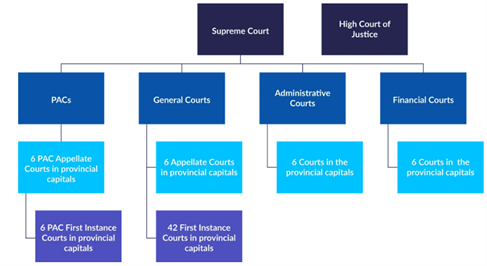

The tree chart below of Madagascar’s anti-corruption judicial process does highlight the odd way in which the HCJ appears entirely detached from the rest of the judiciary, including the country’s Supreme Court:

Courtesy: U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre (Norway)

South Africa: A high-profile landmark case

However, there are some countries that are slowly winning that battle and bridging the gap regarding anti-corruption law. High-profile landmark cases spearheaded by world-class investigations are leading this trend, with South Africa being a good case in point:

Jacob Zuma has been embroiled in ongoing corruption trials, counter-suits and political scandal since his resignation as President of South Africa in February 2018. His nine years in power were riddled with accusations of rampant corruption and grift by the opposition and most of the media, and which culminated in his being jailed for fifteen months in July 2021 by the country’s Constitutional Court, albeit on contempt of court charges. He was released on parole after two months on health grounds. Even that leniency was met with huge controversy and resulted in a high court overturning the parole decision in December 2021 on the basis that it had undermined respect for the judiciary, the rule of law and the 1996 Constitution.

Zuma’s attempts in early 2022 to further delay his corruption trials in 2022 also proved unsuccessful. In late March 2022, the Supreme Court of Appeal rejected all four of his appeals and ruled that Zuma's claims regarding the ‘unconstitutionality’ and ‘political bias’ of his pending corruption trial had "no reasonable prospect of success on appeal and that there are no other compelling reasons for an appeal to be heard". Zuma faces 16 counts of fraud, corruption and racketeering based on allegations that he accepted bribes from the French defence group Thales for a major arms deal back in the late 1990s.

Kenya: Successful corruption convictions

Kenya is another case in point. Although one of Africa’s economic powerhouses, Kenya continues to grapple with endemic and widespread corruption. The ongoing case against the flamboyant and controversial governor of Nairobi, Mike Sonko, offers some hope. Sonko was formally removed from his office in December 2020 by impeachment-type proceedings conducted by the Senate of the Republic of Kenya on 11 charges that included “gross violation of the constitution, abuse of office, gross misconduct and crimes under national law”. That was a year after Sonko had been arrested on suspicion of his direct involvement in a multi-million dollar corruption scandal, including forging documents, misappropriation of Nairobi County funds and awarding tenders to close aides.

However, the country’s director of public prosecutions (DPP) has complained that the investigation against Sonko has been thwarted due to repeated attempts by Sonko and his supporters to obstruct the case. Sonko and his family would later be denied entry into the United States in March 2022 on the basis of the corruption charges against him. Encouragingly, it was reported that there had been scores of successful corruption convictions by December 2021 against Kenyan government officials and businesspeople. This included a businessman who was sentenced in September 2021 to either 27 years imprisonment or a fine of €5.76 million by the anti-corruption court for having defrauded the country’s Youth Development Fund to the value of €1.44 million in 2014. The country’s DPP also scored a major victory when the High Court set a precedent that barred officials from accessing their offices whilst their cases for corruptions were pending.

Discover the trends

Get the full view, including the latest trends, on anti-corruption law across Africa by downloading our report.